By S Jackson

A man walks alone in the Connecticut woods. He sits down to write. He takes a few photos.

What no one would know about this man, if you bumped into him on this summer afternoon, is that he’s a teacher. And as he walks, he’s imagining what he’ll do with his high school students when they are back in his classroom this fall.

He’ll take them outside, he decides. Frequently. They’ll go for walks. He will encourage them to document the world around them by taking pictures or using Google 360, a virtual reality tool, or with just good old-fashioned pencil and paper.

Although he’s alone in the woods, Rich Novack is part of a unique summer collaboration between educators and park rangers. The nationwide program is designed to encourage place-based learning.

Being outside the classroom, in nature, is for Novack a key part of his job as a high-school English teacher. He says leaving the classroom to explore nature helps teach students to “become curious,” a skill they will continue to rely on as critical readers and thinkers throughout their lives.

To be aware as we read, he said, “helps us find those odd, interesting, or observant passages. When we’re out here [in nature], we’re on the lookout for interesting, curious things as well.”

Write Out was a two-week professional development program, sponsored by the National Writing Project through a partnership with the National Park Service. The program connected educators and park rangers with place-based learning opportunities in July 2018. A team of educators from both organizations—educators who have themselves been working on collaborations in their local communities between Writing Project sites and national park sites—designed #WriteOut. Their goal was to help educators make connections between learning, writing/making, and local outdoor and historic public spaces.

The online learning opportunity offered two “activity cycles” that encouraged teachers to experiment with place-based learning and then share what they learned in collaborative online spaces like Google+, Twitter, and online video hangouts.

The themes focused on mapping your community and mapping connections between communities. Activities included community mapping, photographing local parks and public spaces, creating curricula based on local historic places to share with other educators, visiting a local national park, and writing poems. Educators traveling with their families also participated. Jen Dumont, for example, posted her Write Out adventures as she hiked Bald Knob in Moultonboro, New Hampshire.

The National Writing Project is known for a workshop-based approach that encourages educators to get their hands dirty and experiment with activities that they may ask their own students to try.

Kristin Lessard, a park ranger in Connecticut who was on the Write Out planning team, said a key goal of the National Park Service is to educate the public on and find creative ways for people to be inspired by our national parks. Being able to connect directly with teachers through #WriteOut was incredibly valuable, Lessard said.

“We’d done a lot of outreach to teachers. And we have a handful of local teachers who come regularly, but through this partnership we were able to connect to educators from other nearby towns or places that we had been trying to connect to for a while.”

Lessard said that when students learn through this lens of place, learning can be more meaningful. Lessard works at Weir Farm National Historic Site, which commemorates the life and work of American impressionist painter J. Alden Weir as well as other artists. She also overseas Weir Farm’s partnership with the Connecticut Writing Project–Fairfield, of which Rich Novak is a member. In addition to exposing students to American impressionism, teachers use the beautiful landscape to teach other things, like mapping skills, that build on what they’ve learned in class.

“Students are able to solidify their knowledge with experience,” Lessard said. “It brings a whole new level of engagement and learning.”

Lessard said she sees many opportunities for future collaboration between the National Park Service and the National Writing Project. You can see what’s emerged out of the work so far at this collection.

If teachers missed the professional development sessions this summer, there are still ways to get involved. Educators can complete the We Make The Road By Walking Playlist and earn a badge that links to their portfolio of work. They can also share how they “write out” in their classroom and learning space via Flipgrid.

Meanwhile, many of the participating educators are using what they learned this summer by taking their students and colleagues out of the classrooms and into public spaces and parks to write and create.

Margo Wixom, for example, took her photography students from Palo Alto High School in the Bay Area to a local protected space, the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge, to study marshlands and climate change. Andrea Zellner of the Red Cedar Writing Project in East Lansing Michigan organized a writing marathon with her colleagues.

Rich Novack says he plans to have his Environmental Literature class find an outdoor space near their home where they can go outside regularly to write in their field journals and “free write.” Helping students connect with their environment, Novack says, can help them ponder their place in the universe, to experience otherness, and to “reconcile that otherness with coming to love it and appreciate it.”

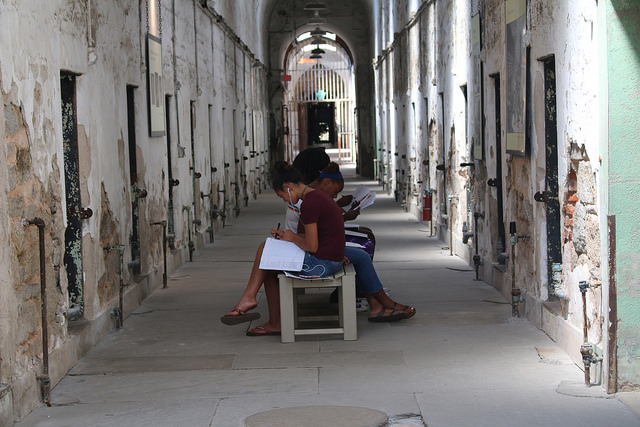

Featured Image: Used with Permission, “Ranger Road” from Weir Farm National Historic Site