Like anywhere in the United States today, the rural Texas town of Bastrop, located about 30 miles outside of Austin, is no stranger to the pervasive narrative of our nation’s “failing public schools.” This deficit-based story of struggling schools, teachers, and students often leads to strict “accountability” regimes and back-to-the-basics teaching–standardized teaching for standardized tests. As a result, says Heart of Texas Writing Project teacher-consultant and co-director Katie McKay, “the way of teaching that is supported by research is under attack.”

While conducting writing workshop professional development for Bastrop ISD, McKay envisioned a way to counter these narratives using a key component of the National Writing Project’s approach to writing: creating opportunities for students to write for an authentic audience outside the classroom. McKay recruited a team of six K-3 teachers who had been particularly enthusiastic about the writing workshop, and set out to establish Choice and Voice: Agency and Audience in a Resilient Rural Texas Community, a 2017 LRNG Innovators Challenge grant project.

The LRNG Innovators Challenge grants are the result of a partnership between LRNG, powered by Collective Shift, the National Writing Project, and John Legend’s Show Me Campaign. The grants support educators and projects that are expanding the time and space for connected learning, a theory of learning that aims to connect school work to students’ passions, peers, and out-of-school worlds.

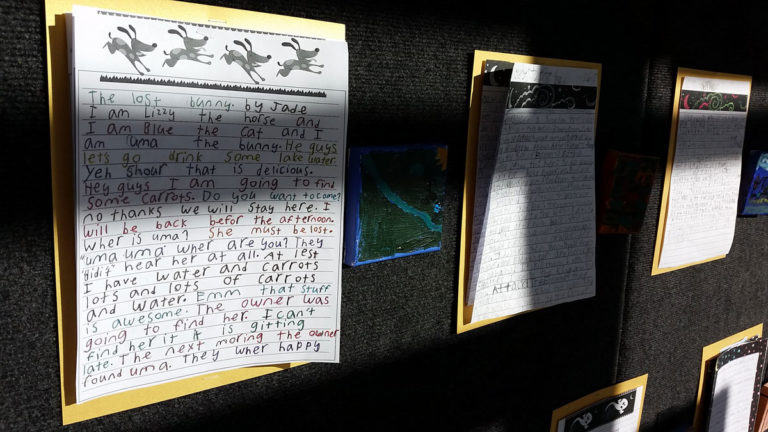

Choice and Voice unfolded in four stages. First, the team came together under the guidance of McKay to each plan two, 4-6 week writing workshop units of study. Next, these units, which emphasized student choice and autonomy, were implemented over the course of the year. Third, both the students’ work and the teachers’ unit plans were published online, using the platform Buncee. Finally, student work was published around the town of Bastrop in partnership with a variety of community organizations and businesses, accompanied by educational research explaining the developmental context of the student work.

Each step in the project brought its own unique benefits, and together they created a whole that has improved the writing craft of young students; ignited the professionalism, connectedness, and passion of teachers; forged new partnerships between schools and community organizations; and pushed back against accountability-based narratives of deficit and failure by showing the community what’s really going on inside of schools, and what young students are capable of when given agency in their own learning.

In creating the writing workshop units of study, the team emphasized two major themes. First, they wanted to combat the deficit belief that young students aren’t ready to learn how to write, that composition and craft can come only after they’ve mastered their ABCs. “We want to show that from the day they enter into schools, they’re capable of crafting original, powerful pieces of writing,” says McKay.

Bastrop Parks and Recreation helped to display more than 100 bilingual kindergartners’ mobiles at the local Fisherman’s Park, incorporating the dangling drawings into the holiday’s River Lights Walk.

To that end, kindergarten teacher, Dr. Guadalupe Chávez ’s lessons focused on drawing as a form of composition, and as an arena for learning author’s craft. The impact of this work was evident later in the year, when the bilingual class produced “informational books,” many of them in Spanish. “It was unbelievable for their informational books, to see how much text ended up on the page, even more than in a lot of classrooms I had seen pushing text early on. It was the fact that Dr. Chávez had spent so much time building their strengths through drawing that they then were able to add that text in,” says McKay.

The other major theme in the units’ design was an emphasis on student choice and autonomy. This too, says McKay, is important to develop early. “Kids have a natural inclination, a natural passion for communicating their stories with us—they know things they want to tell us—but as soon as they get to school they’re often taught that it has to be about the most special day, or the greatest time ever, and it feels like this hierarchy of topics….Instead we have to teach them from the beginning that that choice is what we want to see.”

In addition to the informational books, a second grade class studied the works of author Mo Willems, and wrote their own persuasive texts modeled on his Don’t Let the Pigeon Ride the Bus. Another Kindergarten class produced a digital alphabet book, which was a hit on the Bastrop Public Library’s website. Student work from all 12 of the units of study can be viewed here.

The teachers documented and published their own process and thinking alongside the student work, which changed the way they related to their work, and helped them see themselves as teacher leaders. When classroom practice is documented and shared, McKay explains, it is no longer something happening isolated in a single classroom, but is instead meaningful knowledge, of value to other teachers. “It’s like as soon as we start seeing our work as something that there might be an audience for…we start seeing ourselves as a teacher researcher.”

For the final phase of the project, McKay and the team connected with a variety of community organizations to fill the town of Bastrop with student work. Their queries received an enthusiastic response from the local library and Parks and Recreation department, both of whom have reported an exciting synergy wherein the student work is bringing new people into the library and parks. Student work was also displayed in the Lost Pines Art Center, a new gallery and events space in town, and the famous Berdoll’s Pecan Pie Shop. “These different community organizations…that we partnered with are now saying, ‘what can we do next year?’”, says McKay. “They’re just excited about this continuing to grow.”

In these displays, the team put an emphasis on providing the community audience with the proper developmental context for understanding the work on display, and the growth and craft it represents. In Berdoll’s, for instance, the kindergarteners’ drawings and writing were accompanied by QR codes, linking a viewer to the education research underpinning the idea of drawing as a form of composition.

And this context is key, because for all the myriad benefits to teaching and learning that Choice and Voice provides, perhaps its most important contribution transcends the school building. Politicians, leaders, and community members don’t often get to see what is happening inside of schools, and that lack of information has created fertile ground for an accountability and evaluation system built solely on test scores and deficit beliefs about students, teachers, and schools.

“Our schools are under attack right now, and the way of teaching that is supported by research is also under attack,” says McKay. “So it’s an act of social justice to put student work out there that might push back on the idea that it’s supposed to look perfect.” Sharing student work, when done with intention, can cultivate community pride, and help weave a net of community support for public schools. “If we have good practices in place, it’s the way that we share [the work] that can help us handle our school reputation and image, and push back against tests being the only way that our schools and teachers are evaluated” (you can read more about this from McKay herself on The Current, our open publishing platform for educators).

One of the most exciting parts of Choice and Voice is the momentum it has taken on: in addition to the enthusiastic community organizations that now have experience displaying student work, McKay has heard from scores of teachers who are either colleagues of teachers on the team, or who saw the public displays, and are inspired to either get involved or spearhead similar projects on their own.

Choice and Voice is a shining example of the pride and craftsmanship that is unlocked when students and teachers are given agency and choice in their teaching and learning. By sharing what happens in the classroom with other teachers and with the community, teachers can cultivate professional and community support for public schools, and in particular for the kind of authentic education that truly brings out the best in students. In a situation where public perceptions of schools are guided largely by policymakers with little to no experience in the classroom, Choice and Voice offers a model for how teachers can seize the mic by sharing what’s really happening in public schools, and by allowing the incredible work students can produce to speak for itself.